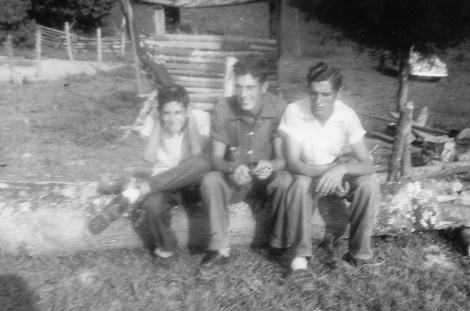

This photo, from the 1950s, includes two of my uncles. My mother’s family lived in the Cumberland Plateau region of south central Kentucky/north central Tennessee — near Albany, Kentucky. They are Scots-Irish. In J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy’s version of Appalachia, all Appalachia residents resemble this image.

As a family historian I have researched my (mostly) Appalachian roots so I feel somewhat knowledgeable about the culture. Although my paternal side is English, my maternal side is Scots-Irish (Beaty). But personal knowledge can be a small window to peer through so I seek out broader works to better understand my heritage.

Like many, I read Hillbilly Elegy by J.D. Vance. However, unlike many, I was not impressed with it.

I live in the region Vance details in the book. Preble County, is directly north of Butler County where much of the memoir is set. Preble County is mentioned several times and my favorite quote — with just a little tweaking — says,

When I was about nine years old things began to unravel at home. Tired of Papaw’s presence and Mamaw’s ‘interference’ Mom and Bob decided to move to Preble County…Even as a boy, I knew this was the very worst thing that could happen to me.

Despite the acceptance of Elegy, much like the tweaked quote above, the book does not resonate as an accurate depiction of Appalachia or ‘hillbillies’ in southwest Ohio. When I reviewed Elegy I included comments from Jacobin which provided a much-needed context to the Middletown, Ohio dilemma (and other regions of the country) Vance highlights. The Jacobin review mentions the entrenched systems that prevent upward mobility, a segment of the story that Vance conveniently omits. Or, as the review states in its pithy subhead: The American hillbilly isn’t suffering from a deficient culture. He’s just poor.

As I tried to understand Elegy’s runaway success, I stumbled onto a blog by Elizabeth Catte, and learned about her upcoming book: What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia. Her blog revealed she was from Appalachia but more importantly, she was committed to a realistic representation of the culture. So I preordered her book, and found in it an author who, unlike Vance, is not attempting to package a nice ‘clean’ (i.e. profitable) version of Appalachia.

As I tried to understand Elegy’s runaway success, I stumbled onto a blog by Elizabeth Catte, and learned about her upcoming book: What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia. Her blog revealed she was from Appalachia but more importantly, she was committed to a realistic representation of the culture. So I preordered her book, and found in it an author who, unlike Vance, is not attempting to package a nice ‘clean’ (i.e. profitable) version of Appalachia.

First, The Basics

The book is succinct — less than 150 pages — but the size is deceiving because a lot of interesting content is packed in between the covers. The book is divided into three parts.

- Part One: Appalachia and the Making of Trump Country.

- Part Two: Hillbilly Elegy and the Racial Baggage of J.D. Vance’s Greater Appalachia.

- Part Three: Land, Justice and People

I have read both Elegy and Appalachia, and for those interested in educating themselves, Elegy pales in comparison to Appalachia. Elegy is a modernized Horatio Alger story that re-manufactures an all-white culture too lazy to solve its own problems, whereas Appalachia rejects the stereotypes and reports objectively on the region.

Part One: Appalachia and the Making of Trump Country.

Catte opens with the national media’s interest in Appalachia during the 2016 presidential campaign. In one telling section she dissects the national media’s assertion that McDowell County, West Virginia was a ‘Trump County.’ She references, among other sources, a Huffington Post article which asserts McDowell County offers a ‘glimpse at the America that voted Trump into office.’

As Catte notes, the media declared the county a ‘landslide’ victory for Trump. McDowell County, which had 17,508 registered voters in the 2016 presidential election, cast 4,614 votes for Trump and 1,429 for Hillary Clinton. As Catte says,

“if we use reported numbers we find that only 27 percent of McDowell County voters supported Trump.”

Besides the fact that in ‘Trump County’ a significant percentage of the voters stayed home, Catte further counters the ‘Trump County myth’ by revealing these facts about West Virginia — truths that defy stereotypes. For example:

- West Virginia has the highest concentration of transgender teens in the country.

- in 2017, filmmakers in West Virginia hosted the fourth annual Appalachian Queer Film Festival.

- More people in Appalachia identify as African American than Scots-Irish.

As she ends this section of the book, she segues into Part Two reflecting on her college years.

“While reading Greek poetry, my professors warned us to be careful of the double meaning of elegies; they were, it seems, often written as political propaganda.”

Part Two: Hillbilly Elegy and the Racial Baggage of J.D. Vance’s “Greater Appalachia”

As Catte states, the concept of a Greater Appalachia, is not an original idea by Vance. The term is usually associated with Colin Woodard who uses the phrase in American Nations. I would argue, based solely on personal experience, that the Vance family’s migration to Middletown is fairly common in southwest Ohio. Butler County, and Preble to the north does have a heavy Appalachia-based population. But, as Catte accurately notes, Vance’s version of Appalachia is all white — which does not accurately depict Appalachia (or Butler County for that matter). This is especially true of the officially designated region of Appalachia which boasts significant African American and Hispanic populations.

But, she opens this section with the story of the 1968 killing of a Canadian filmmaker who was shot by a well-connected Jeremiah, Kentucky landowner. The landowner is eventually convicted of involuntary manslaughter – serving one year in prison. She uses the story to segue into the exploitation Appalachia residents have faced over the centuries — often accomplished through ‘poverty images.’ She notes,

“Much like the visual archive generated during the War on Poverty, Elegy sells white middle-class observers an invasive and exploitative story of the region. For white people uncomfortable with images of the civil rights struggles and the realities of Black life those images depicted, an endless stream of sensationalized white poverty offered them an escape …”

For me, this section of the book is the strongest as Catte builds her case against Vance’s work. I do not want to retell her arguments because I sincerely hope people purchase her book to counter the myth perpetuated by Vance’s work. (For the record, I do not know Ms. Catte and will not financially benefit if her book sells. As a human, tired of myth creation in America, I simply want a more accurate depiction of Appalachia to be read.)

Part Three: Land, Justice and People

Catte wraps up the book building on the photo motif. She describes images of individuals significantly more representative of Appalachia than Vance. This is the section for people who truly want to meet the people who are, unlike Vance, doing work that benefits the community. The individuals range from photographers to community organizers. This section also sheds light on why, and how, the War on Poverty from the 1960s ultimately failed.

Although in this section she does rehash some fairly well-known stories, like the Harlan County, Kentucky strike and Matawan, she also includes numerous lesser-known events like an arsonist attack on Mud Creek Health Clinic. She also touches on the failed promise of political leaders in the current era concerning the private prison industry. In the 1990s, two large prisons opened in southwest Virginia and with them the promise of ‘good paying local jobs.’ As she notes, though, local workers did not receive the ‘good jobs’ instead the ‘locals’ were regulated to low-paying, menial labor positions.

My Rating: 5 out of 5. One of the sad realities of life in the United States is the books that should hit the bestsellers list — this one — will not while those that perpetuate a myth — Hillbilly Elegy — do. Besides being an engaging read, Appalachia, is also a heavily researched ‘textbook.’ Included in the book is a section of 8-10 pages of resources and suggested reading. Although it may not be important to everyone, it is to me, as I read Appalachia, I feel Catte actually cares about Appalachia and is interested in its progress. This is a stark contrast to Elegy’s author who is simply pushing a popular, but exploitive, political agenda.

Church, located in Cumberland County Kentucky, bears my surname. The church is located about two miles from my father’s childhood home.

One of the United States’ first acts of war, The War on Tripoli (1801-1805) is largely unknown. I became interested in it because my hometown, and county, are named after some of the conflict’s key players. It was the country’s first significant win at sea and the founder of Eaton, Ohio — William Bruce — used the patriotic fervor to get a county created.

One of the United States’ first acts of war, The War on Tripoli (1801-1805) is largely unknown. I became interested in it because my hometown, and county, are named after some of the conflict’s key players. It was the country’s first significant win at sea and the founder of Eaton, Ohio — William Bruce — used the patriotic fervor to get a county created.

As I tried to understand Elegy’s runaway success, I stumbled onto a blog by Elizabeth Catte, and learned about her upcoming book:

As I tried to understand Elegy’s runaway success, I stumbled onto a blog by Elizabeth Catte, and learned about her upcoming book: